Our Czech Connections

Look inside our Ark and you will discover a very special piece of history! Sobeslav Scroll number 1211.

Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, the European Jewish communities experienced persecution and anti-Semitic uprisings, and yet they still found ways to flourish and create communities. One of these places was Sobeslav, a small village in the Tabor region of Czechoslovakia.

Our Sobeslav Scroll 1211 (Cz 57071) is one of the 1564 Czech Scrolls that were saved in Prague during the Holocaust of World War II, when hundreds of Jewish communities in the Czechoslovakian regions of Bohemia and Moravia were destroyed or abandoned. Their religious objects were collected and stored in the Jewish Museum in Prague. The Torah scrolls from Czechoslovakia were part of a huge collection of Jewish ceremonial and cultural objects that were collected at the Jewish Museum at the instigation of the leaders of the Prague Community. There, the Jewish curators who worked at the Museum, sorted, classified, and catalogued these treasures and arranged the scrolls in stacks reaching from the floor to the ceiling. Although under the control of the Nazis, the museum workers were subject to a surprising lack of supervision. But, for the Jews thus employed, it was a short reprieve; even before their task was completed, they were deported and all but two eventually perished in the death camps.

When World War II ended, the Torah scrolls still at the Museum, were moved to the Michle Synagogue in a suburb of Prague. However, nothing could be done to preserve the Torah scrolls from deteriorating in the damp conditions. To keep parchment scrolls from perishing, they must also be rolled from time to time. This was patently impossible to do with over 1,500 scrolls housed in desperately cramped quarters. And so, the scrolls seemed condemned to slow decay.

The Scrolls journey to England

In 1963, officials at Artia, the state corporation responsible for the export and import of cultural articles, approached Eric Estorick, a well-known London art dealer, on one of his visits to Prague and asked him if he was interested in purchasing Hebraica and he was taken to the Michle Synagogue. Estorick’s response was positive. Estorick discussed the problem of the Czech scrolls with one of his clients, Ralph C. Yablon, a well-to-do, public-spirited member of London’s Westminster Synagogue and philanthropist. Yablon in turn contacted his rabbi, Harold F. Reinhart, who had been contemplating the idea of setting up a Holocaust memorial museum in his synagogue. Perhaps, the rabbi said, some of the Czech Torah scrolls could be brought to London as a nucleus for such an exhibit. Yablon was interested, but first he said that an expert would have to make an on-the-spot inspection of the scrolls to determine their condition; more specifically, to see which of them were still ritually fit for use in synagogue services. He knew of such an expert in London, Chimen Abramsky, a historian and acknowledged authority on Hebraica and Judaica.

Arrangements were made for Abramsky to go to Prague. His preliminary examination of about 250 scrolls found them without protective covering. Others were swathed in tattered prayer shawls. He found two scrolls wrapped in a woman’s garment. Another was tied with a small belt from a child’s coat. A shocked Chimen Abramsky reported that the collection of scrolls was genuine, though many of the scrolls were in bad condition. Yablon instructed Estorick to negotiate the purchase of the collection. Eric Estorick negotiated with Artia to acquire the 1,564 scrolls from Communist Government of Czechoslovakia for the equivalent of £30,000, and in December 1963 the Westminster Synagogue became the official trustee for the entire collection until such time as it could be distributed elsewhere. In addition to purchasing the scrolls for the Westminster Synagogue, Yablon supplied the funds for their packing and their transportation from Prague to London.

The first consignment of the collection of Czech Memorial Scrolls arrived at Westminster Synagogue in February 1964. Having catalogued, classified and restored the scrolls, where possible, the Memorial Scrolls Trust was established and sent more than 1,400 scrolls, on long term loan to synagogues and institutions throughout the world.

Our Sobeslav Scroll was originally allocated by The Memorial Scrolls Trust in 1971, to Polack’s House, Clifton College, Bristol. It was retrieved from Clifton College in 2008, having been found not to have been in use for some time.

The Sobeslav connection

Hendon Reform Synagogue had originally been allocated Scroll 1457 and Rabbi Arthur Katz had been given to believe by Rabbi Harold Reinhart that it was specially chosen because it was said to have come from the town of Sobeslav where Rabbi Katz had been its last rabbi. In fact, the records revealed in around 2005 that Rabbi Reinhart had been mistaken and that Scroll 1457 had been received from the town of Tabor, which is near Sobeslav. The error was discovered long after the death of Rabbi Arthur Katz, by which time his son Rabbi Steven Katz had taken over from his father as the rabbi at Hendon Reform Synagogue.

Michael Heppner, the research director of the Memorial Scrolls Trust, was aware of this case of mistaken identity and when, by chance, Scroll 1211 was returned from Clifton College he proposed to rectify the error by offering it to Rabbi Katz in exchange for the Tabor Scroll. Thus, the gesture that Rabbi Reinhart had intended would be made good. The exchange was made on 26 March 2008 on condition that Hendon Reform Synagogue would arrange for a Sofer to examine Scroll 1211 and carry out any refurbishment that was necessary. The scroll was examined by Sofer Stam Bernard Benarroch who carried out the necessary work that year. The MST records show that it probably was originally written around 1900.

When Hendon Synagogue merged with Edgware Reform Synagogue to form Edgware and Hendon Reform Synagogue in 2017, Scroll 1211 from Sobeslav was brought to the Edgware synagogue and the Memorial Scroll from Golcuv Jenikov that had originally been allocated to Edgware Reform Synagogue was returned to the Memorial Scrolls Trust and allocated to a new congregation.

There are eleven other Sobeslav Scrolls with other congregations, and these are all in the USA. What all twelve congregation have in common is the responsibility which comes with being entrusted with a Memorial Scroll, and that is to honour and remember as individuals the Jews of their lost congregation, as we ourselves would wish to be remembered, and to save them from the Anonymity of the Six Million.

To find out more about the Memorial Scroll Trust click here.

The Sobeslav Jewish Community

Jews came to Sobeslav at the beginning of the 16th century, but in 1606 they were expelled and no longer permitted to live in the town, although they were allowed to trade there. They moved to nearby villages. Only after the 1848 revolution gave equality to the whole population did the Jews return to live in Sobeslav. Despite anti-Jewish riots in 1866, they built a thriving community establishing successful clothing, grocery and liquor shops and factories.

The synagogue housing the Torah we now have, and a school were built in 1874. By 1910, there were 121 Jews in Sobeslav. They mostly spoke German. The commercial success of the Jewish community and their preference for speaking German alienated the local population, resulting in more anti-Jewish riots in 1911. But after World War I the German language disappeared from the streets of Sobeslav.

Between the world wars the Jewish community thrived, until the German occupation in 1939. The Germans introduced anti-Jewish laws, so Jews could no longer practice their faith or attend public restaurants, theatres and swimming pools. Jews had to wear a yellow Star of David. In 1940, Jewish shops and the synagogue were closed.

On the 16th of November 1942, all the Jews, alongside others from surrounding villages in the Tabor region were deported to Theresienstadt (in Czech Terezín) and in 1943 to Auschwitz to be murdered. Only a few residents are known to have survived, 70-year-old Berta Kreisslova and five-year old Pavel Wurmfeld. Their Rabbi, Dr. Arthur Katz, was fortunately out of the country at the time of the deportations, however his wife perished in Auschwitz. A member of one of the most prominent Jewish families, who owned an important factory, was one of 13 Jews who were spared immediate deportation because of intermarriage status. Josef Blann, who was married to Milada, a non-Jew, was deported a year later and sent to the Oslavany labour camp and the Kukla mine. His 14-year-old daughter, Noemi, was sent to Theresienstadt. They survived and were liberated in 1945 and returned to Sobeslav, where Milada still lived. The other Jews with intermarriage status were not rounded up until a few months before the end of the war and went no further than Theresienstadt.

Sobeslav today

The synagogue was used as a storehouse until it was torn down in 1959. A building for the town’s office of communal services was established there. Today it is a private residence.

In November 2015, and with the assistance of Julius Muller, founder of the genealogy organization Toledot, and a leader of the Jewish community in Prague, an American synagogue, Temple Beth Shalom, who also hold one of the Sobeslav Scrolls, sponsored a bronze plaque and arranged for it to be erected on the outer wall of the private residence. After 70 years, in a moving ceremony, the Jews of Sobeslav were memorialized, and Hebrew was heard on Jew Street again. The TBS plaque bears witness to the lives and cruel end of the Sobeslav Jewish community, click here to read more.

In May 2024, Rabbi Tanya Sakhnovich, and a group of our EHRS members, visited the site with Julius Muller. They were joined by Michael Makovec who is the grandson of Josef Blann, Michael’s family, and Dana and Monika Slaba, who are the current occupants of the private residence. Together, they recited and sang memorial prayers to honour the memories of the lost Jewish community of Sobeslav. The group were later welcomed by Mayor Jindřich Bláha, and they look forward to deepening this friendship in the future .

The EHRS group also visited the old Sobeslav Jewish Cemetery, which is located some 4 kilometres outside of the main town, and is now only accessible by foot, through an overgrown forest. There, they recited Kaddish and saw that even though Sobeslav today has no Jewish population, there was evidence that visits to the cemetery do take place, as there were quite a few pebbles/stones placed on several of the headstones.

The Missing Neighbours Project

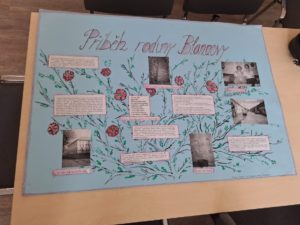

In 2001, students in the Sobeslav gymnasium (high school) participated in a project organized by the Jewish Museum of Prague to remember victims of the Holocaust. Under the leadership of teachers Petr Lintner and Radim Jindra , the students researched the lives of the Sobeslav Jewish residents and what happened to them. They even retraced their deportation to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. Their research culminated in a well-regarded exhibition that brought their work to the Sobeslav public. Jindra was invited to Yad Vashem for his contributions.

The EHRS group met with Radim, and were shown some of the wonderful work that had been produced for the project.

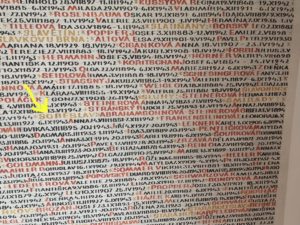

The Jewish Museum in Prague maintains a database of Shoah victims from the Czech lands online under the name “Digital Extension of the Pinkas Synagogue”.

If you enter “Sobeslav” in the search box , you will see a total of 63 Shoah victims who had Soběslav as their last address before deportation, click here.

In 2023, in cooperation with the State District Archive in Tábor, the museum managed to obtain photographs of many of the victims, taken from id documentation, which they have added to their database. When you click on a particular person, you will be able to access this data, including information about the transports.

Their names are immortalised on the walls of the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague.

EHRS has a proud history that goes back to 1935. Now, having embraced the Jewish community of Sobeslav through being entrusted with the legacy of one of their Torah Scrolls, we have a community history that stretches back to the 16th century. As individuals we come from a scattered heritage across Europe, but the Scroll from Sobeslav offers us insights into one community’s history that we now all share, and which helps us to identify with the fate of those Jews in a personal way.